[ the main topic page ] [ the main page ]

![]()

Ph.D. Igor I. Kondrashin - philosopher

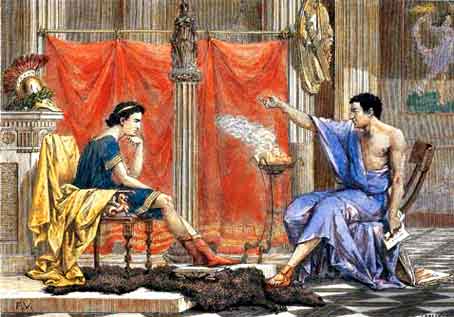

"The two Ancient Greek traditions: the first one is revived about 100 years ago.

The time came to revive the second one and make it innovative."

![]()

[ the main topic page ] [ the main page ]

![]()

Ph.D. Igor I. Kondrashin - philosopher

"The two Ancient Greek traditions: the first one is revived about 100 years ago.

The time came to revive the second one and make it innovative."

![]()

Coubertin built on the ideas and work of Brookes and Zappas

with the aim of establishing internationally rotating Olympic Games that would

occur every four years. He presented these ideas during the first Olympic

Congress of the newly created International Olympic Committee

(IOC). This meeting was held from June 16 to June 23, 1894, at the

Sorbonne University in Paris. On the last day of

the Congress, it was decided that the first Olympic Games, to come under the

auspices of the IOC, would take place two years later in Athens. The IOC

elected the Greek writer Demetrius Vikelas as its first president.

The first Committee consisted of 12 members. Now 82 members of the International Olympic Committee

control the affairs of all member countries which joined the Olympic movement.

Coubertin built on the ideas and work of Brookes and Zappas

with the aim of establishing internationally rotating Olympic Games that would

occur every four years. He presented these ideas during the first Olympic

Congress of the newly created International Olympic Committee

(IOC). This meeting was held from June 16 to June 23, 1894, at the

Sorbonne University in Paris. On the last day of

the Congress, it was decided that the first Olympic Games, to come under the

auspices of the IOC, would take place two years later in Athens. The IOC

elected the Greek writer Demetrius Vikelas as its first president.

The first Committee consisted of 12 members. Now 82 members of the International Olympic Committee

control the affairs of all member countries which joined the Olympic movement.

*

* *

![]()

![]()

[ the main topic page ] [ the main page ]